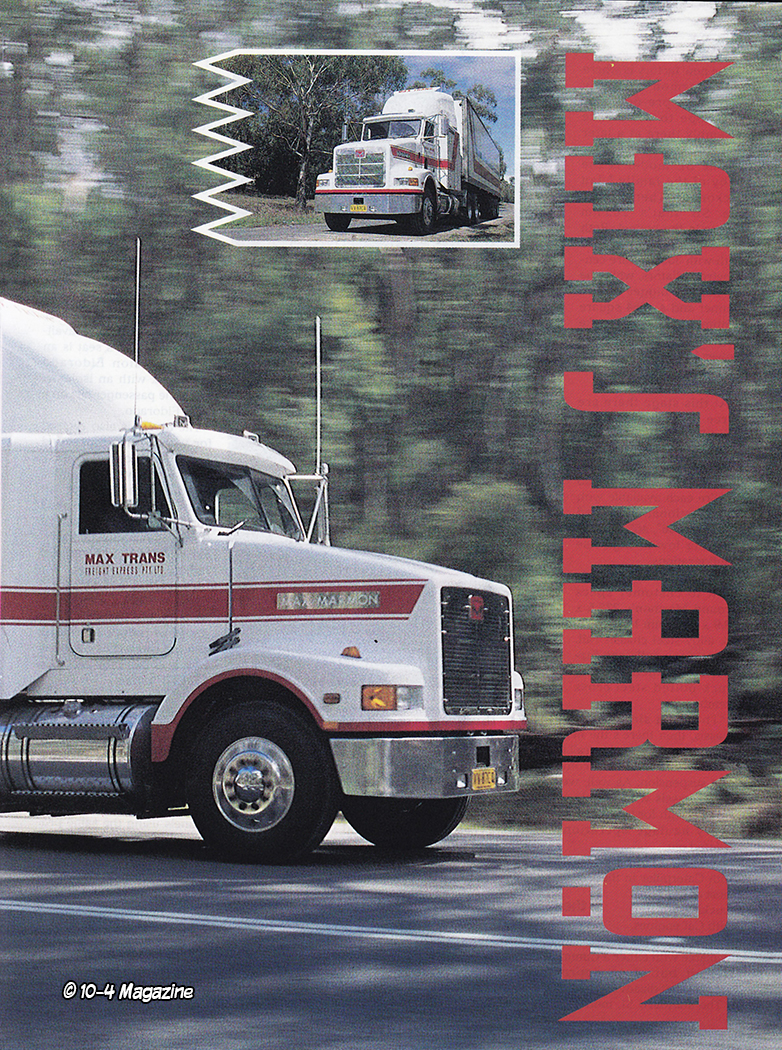

Way back in 1994 a Marmon truck was entered into the Warragul Trucks in Action Show in Victoria, Australia. This was in accordance with a new brand licensing arrangement with Marmon Trucks of Texas, and this truck became known as the “Max Marmon” – the Australian version of the iconic hand built American truck, which was being marketed by a man named Peter Max of Max Marmon Pty Ltd, Victoria.

A year later, in 1995, a Marmon SP model, in a road train configuration, was shown at the Brisbane Truck & Machinery Show in Australia, entered again by Peter Max. The truck had a 500-hp Caterpillar 3460E with an Eaton 18-speed gearbox. There was enough interest shown in the truck to delight the transport operator and business entrepreneur. Prior to this, Mr. Max had visited the Marmon plant in Texas two years earlier to see for himself how the trucks were put together. He liked what he saw and negotiated with Marmon for about 12 months to become the exclusive distributor for Australia, New Zealand, and New Guinea.

In 1995, Peter Max started to import some of the already assembled trucks into Australia. In his workshop facility at Yarraville, Victoria, the first trucks were converted to right hand drive. Later, Marmon shrewdly shipped the trucks as bespoke, right hand drive.

Max initially imported 26 trucks which were made up of the SL, SB, and SP models, just like the U.S. product line. Back then in Australia, conventional styled trucks made up about 73% of heavy duty truck sales. In comparison to the USA, the same manufacturers were in the Australian market, and achieving a market share there was just about as demanding. Was there room for another make of truck or was it a case of the more the merrier? Only time would tell.

One particular Marmon model which became popular with Australian haulers was the SL103. This had the 10-liter 6-cylinder Caterpillar 3176B with an output of 325 horsepower. The transmission was made up of an Eaton RT 12710B Super-10 transmission and Rockwell RT40-145P double drive rear axles. The rear bogie had a Hendrickson airbag suspension. The SL103, which was classed as the smallest of the range, had a basic price tag of $182,500 (in Australian dollars). At today’s exchange rate, that would be about $117,000 in U.S. dollars. Of course, the truck could be specified to the customer’s personal requirements, at an extra cost.

All the trucks sold, which totaled around 33, were fitted with chrome Max Marmon badges on each the side of the hood. Marmon in the U.S. had a close relationship with Caterpillar in regard to their engine provisions, but the Max Marmon company could also supply optional Cummins and Detroit motors at an extra outlay of $10,000 (AUD).

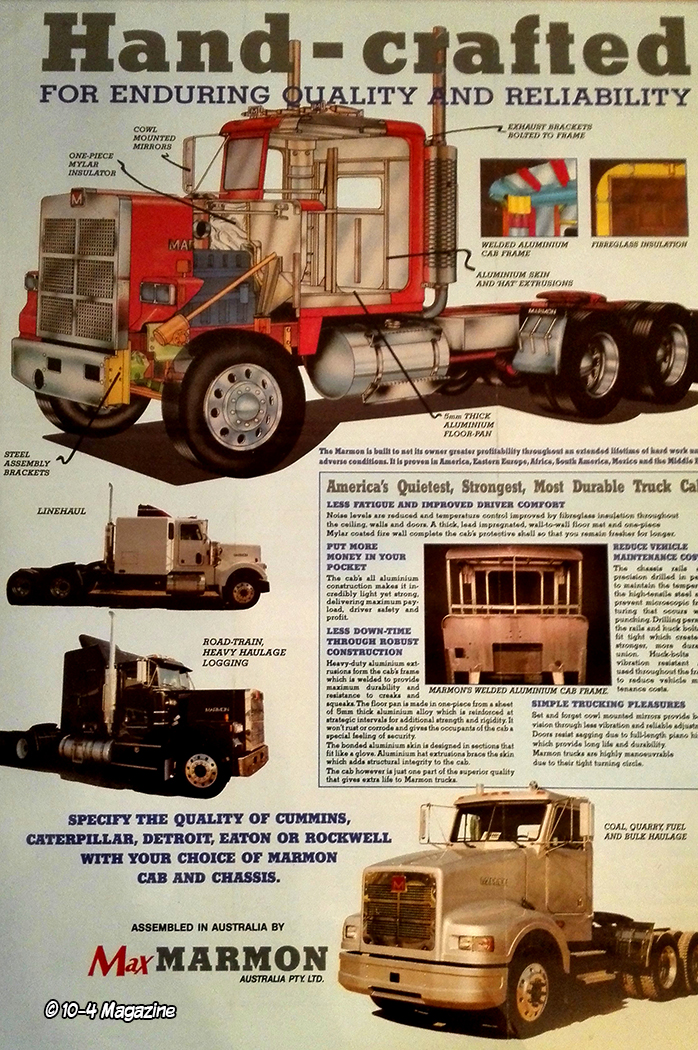

Australian operators liked the build of the cab structure, which was made of aluminum sheet welded over aluminum extrusion framing. This build technique meant the cab was quieter compared to panels fixed together with rivets. They also liked the traditional style of finish, which was thought exceptional for an American truck of the day, and also its cab-mounted mirrors, that didn’t shake compared to the door mounted variety. Another plus point was the ruggedly built, high tensile chassis rails with Huck bolt cross member assemblies.

The Max Marmon range consisted of the long hood and big radiator SP, a pair of sloped hood models with set-back front axles, the SS and SL, and another sloped hood model with a set forward front axle. Over the range of options, engine outputs were available from 400-hp to 550-hp, and a typical SP was priced around $230,000 (AUD) with all of the additional options.

Two years later, in 1997, things changed dramatically when the Marmon operation in Texas ceased to function properly. This was a shot out of the blue for Peter Max because a month earlier he had contacted Marmon to ask if they were happy with his distribution. A big thumbs up came back and, because of this, he began making plans to sell two of his other businesses to concentrate on selling more of the trucks. This goes to show that a lot can happen within a month, especially in the transportation business, which can be volatile. This new situation turned out to be the end of the story for Max Marmon.

Recently, Peter told me that many of the trucks he sold are still working. He also told me that he regretted not keeping one of the trucks for his own business. He said, “I have, on many occasions, tried to buy a truck on the secondhand market, but with no success!” The U.S. Marmon business was sold to competitor Navistar and the Texas plant was then reorganized to build their Paystar line of trucks. Marmon, just like its predecessor Marmon-Herrington, had existed for around 30 years, and fate had dealt a cruel blow to both companies. Max Marmon was the new kid on the block and it oozed potential. Had things been different, there is no doubt that a lot more Max Marmons would be operating in the Southern Hemisphere today.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Big thanks to Peter Max, BTP, B.C. Riley, Frank Tyson, and Russell Frost for providing most of the photographs for this feature.