Though our “Trucking Around the World” articles focus on trucking outside of the United States, there are locations within our republic unique enough in their logistical and operational modus operandi that it is not a stretch to consider such trucking “foreign” to that of the typical over-the-road trucker rolling down those concrete slabs of the continental forty-eight. Alaska is one of those locations.

As the 49th state into our union, Alaska is geographically isolated from the lower forty-eight by British Columbia and the Yukon Territories. A pioneer state largely built on natural resource development, Seward’s Folly is often referred to as the “Big State” – and, indeed, Alaska is big. Larger than Texas in breadth and depth, Alaska’s vastness is punctuated by how remote and sparsely populated the region is. You could fill volumes of books detailing the history, the demands, and the reality of trucking in Alaska. In what limited space I have, I will be selective and impressionistic for this feature, based on my own personal experiences of trucking in Alaska.

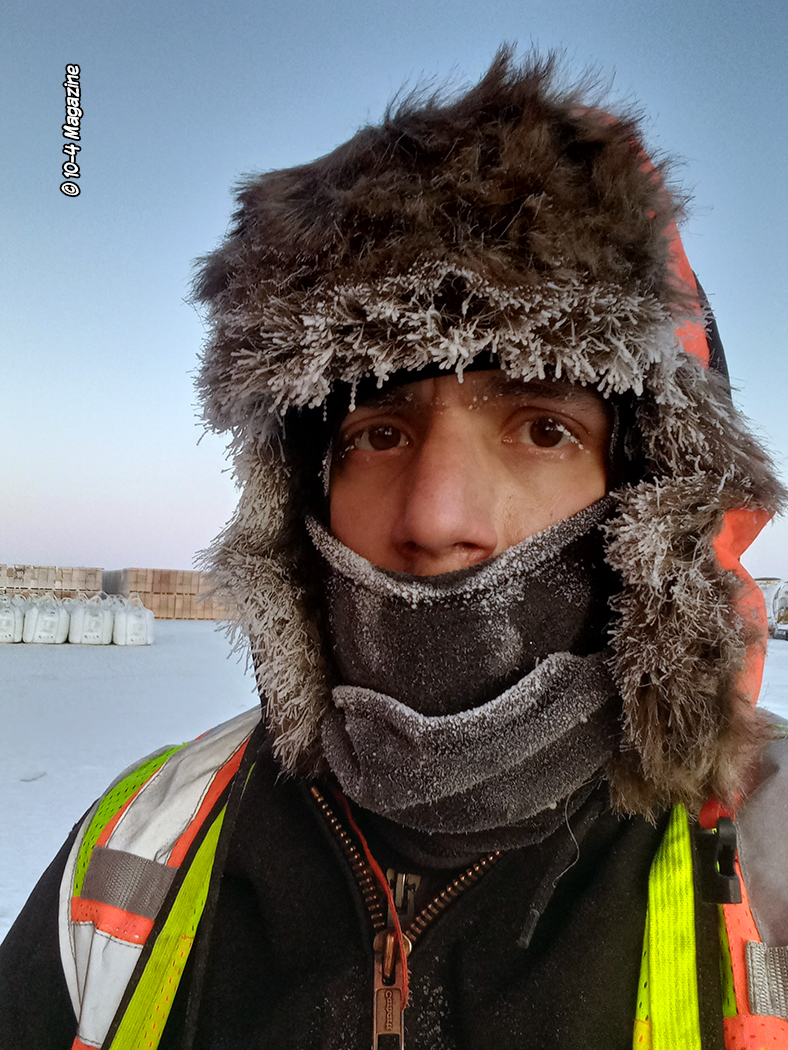

I’m no veteran to Alaskan trucking, as of yet a Cheechako (a newcomer to Alaska), and still very far from being a Sourdough (a long-time Alaskan). The Haul Road, which was formally known as the Dalton Highway, begins about 70 miles north of Fairbanks at the Elliot Highway and continues for roughly 400 miles to Deadhorse near the Arctic Ocean – and it is mostly unpaved. A former lease-road which runs along the course of the Alyeska Pipeline, which was completed in 1977, this engineering marvel feeds crude oil from the rigs dotting Prudhoe Bay and the Beaufort Sea, clear to its final destination – a terminal in Valdez. This road is the main artery to northern Alaska, and it provides amazing views from the driver’s seat around almost every corner.

While traveling the Haul Road, callouts are used such as “Northbound One Mile” and “Northbound Beaver Slide” and “Southbound Atigun, starting from the bottom” – these callouts are the way truckers on the road let each other know what’s happening. Trucks running the Haul Road are equipped with both CB radios and VHF “big radios” that allow all the drivers to communicate extensively. There are no overhead signs or message boards that inform drivers when to chain-up or where wrecks are. The Haul Road is one of the last locales with a significant (though not universal) radio culture, whereby drivers keep each other informed of impending hazards ahead and road conditions.

As a driver, you learn the hills, not simply driving them, but calling them out, so nearby trucks are aware of your presence. With narrow stretches, blind gradients and corners, whiteouts and blizzards, cognizance of the traffic that is nearby is a must. There are several verbal lexicons to the Haul Road that include “wiping your feet” (breaking traction while on a hill but not stalling), “burning out” (breaking traction on a hill and stalling), a “blow” (whiteout from wind), and “barefoot” (no tire chains).

Before running the Dalton solo, at least for any of the Alaskan-original trucking operations, you’ll be paired with veteran drivers on the road. It is over 400 miles of climbs and descents far steeper than most found in the lower 48, primarily over snow and ice in the winter, and mainly mud and dirt during warmer periods of the year. Drivers must learn to read the traction, which includes what might be ahead of them, know the turns and hills, pull outs, and safe stopping points. The mindset of running the Haul Road is all about safety – from One Mile on the Dalton and beyond, the names on the doors of the trucks mean less. It is a dangerous road, and the drivers on it know that, and competitor or not, if a driver needs help, help is given. Ultimately, we seek to ensure all of us get home safely.

If you drive a truck in Alaska, you will get very familiar with tire chains, even if you aren’t running the Dalton. If hanging iron isn’t your scene, you need not apply. The most prevalent chains are three-railer ice-chains, meaning each tire chain covers both inner and outer tires in a dual arrangement, with crosslinks sporting an extremely aggressive stud, allowing the tire chains to bite into snow and ice. Weighing in at 80 pounds per tire chain, the term “hanging iron” certainly has applicability to Alaskan trucking in comparison to the popular single-rail highway chains in the lower 48 States (chains that only cover a single tire with standard oval crosslinks).

For those of you who have been following my articles over the years, you will likely recall much of my albeit short thus far career has been focused on specialized hauling, including winch trucks, lowboys, oversize, wreckers, and towing. Although I am only 32 years old, I already have nearly one million miles of specialized transport under my belt, but the rules and procedures of Alaskan specialized logistics are wildly unique – and I am still learning – but I love the challenge.

When the ground is frozen, Alaska DOT will issue permits with axle weights that would give most other state DOT aneurysms – I’m talking in the 350,000 to 400,000 pound range! Pilot cars are required sooner, too. Most of the roads in Alaska are a single lane only in each direction, meaning width is a concern. For someone accustomed to running 12-feet and 14-feet wide loads without pilots, having a pilot car with only a 10.5-feet wide load is an adjustment. Conversely, as the ground thaws and softens, seasonal weight restrictions can precipitate multi-axle arrangements for surprisingly small machine moves.

No one does heavy haul better in Alaska than Specialized Transport & Rigging. STR Alaska, with terminals in Big Lake (just north of Anchorage) and Fairbanks, as well as Tacoma, WA, is a company built on decades of heavy haul experience, from management to the drivers, from the top to the bottom. With equipment ranging from stepdecks, flatbeds, multi-axle beams and decks, landolls, lowboys, tandem necks, winch trucks, tailroll trailers, and modular and stretch trailers, STR is the name when it comes to Alaskan heavy transport. STR also has a significant fuel transport division, STR Logistics, that primarily serves the fuel needs of those on the North Slope of Alaska (the region north of Atigun Pass and the Brooks Range where Deadhorse, Prudhoe Bay, and other regions of oil development lie).

And, when Alaskan heavy haul mobilizes, it goes big. Due to all the extreme conditions of transporting loads on the Haul Road, outsized transports often necessitate push-pull multi-truck arrangements. It is common to see groups of two, three and four trucks moving large vessels on the Dalton, and lately I’ve had the opportunity to develop my own skill set for push trucking. Like many other aspects of Alaskan trucking, however, push trucking in Alaska has a stark difference versus its counterpart in the lower 48 States.

In most states, when push-pull arrangements are required, the power units are positively connected with drawbars, making for singular units. But, because of the unique traction and geographic complexities present on many Alaskan highways, especially the Haul Road, Alaskan push trucks do not regularly utilize drawbars. Instead, push bumpers, large steel frameworks with heavy-duty rubber padding, are mounted to the front bumpers of push trucks, with trailers and push decks often having push blocks, resembling those found on the rear of scrapers doing dirt work, to be shoved against. Push trucks can be tractor trailers with nose-heavy loads or rigid arrangements with a push deck, a short flatbed, with heavy counterweights placed directly over the drive tires.

Because the push trucks in Alaska lack a positive connection to the primary transport, this requires the driver to learn to actively run into the trailer. Naturally, the goal is to do this as smoothly as possible, but at speeds up to 35 mph, exceedingly rough roads, and constantly changing weather, occasionally “party fouls” may be felt! Communication is key, with drivers and pilots continuously working as a team, to ensure transports upwards and beyond 400,000 pounds can be successfully completed.

I consider myself lucky to call STR home. I love a challenge, I love to learn, and I love specialized work, and no company in Alaska approaches the opportunities for those ends like STR. I am no veteran to Alaskan trucking, but I’d like to thank some who have brought me in and helped me, including Curtis Spencer, Gene Carlson, Ken Griffin, Cody Hyce, Andy Yecny, Ryan Butler, Kevin Kean, Morgan Phillips, Keri Allen, and the many veteran drivers who guided me on my first trips up the Dalton, like Phil Kromm, Adam Schwartz, James Griffith, Jake Evans, Russ and Cory Frantzich, and Luke Leavitt. As they say out on the Haul Road, “Let’s turn up the wick!”