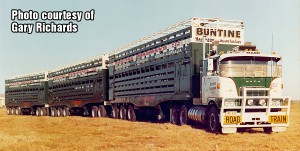

Everyone has heard the stories and seen the pictures of the amazing ‘road trains’ that run across the dry, hot and barren Australian Outback, but few know how it all got started. Last month, we introduced you to Australian Outback delivery specialist Agnes Buntine, a famous female bullock driver (a team of oxen that pulled a wagon) in the late 1800s, and, at the end, mentioned her great-great-grandson Noel Buntine, one of the original road train pioneers of the mid-1900s, when the trucks replaced the bullock teams. This month, we want to continue the story, but focus on Noel and his accomplishments of taming the harsh Australian Outback in a truck.

Everyone has heard the stories and seen the pictures of the amazing ‘road trains’ that run across the dry, hot and barren Australian Outback, but few know how it all got started. Last month, we introduced you to Australian Outback delivery specialist Agnes Buntine, a famous female bullock driver (a team of oxen that pulled a wagon) in the late 1800s, and, at the end, mentioned her great-great-grandson Noel Buntine, one of the original road train pioneers of the mid-1900s, when the trucks replaced the bullock teams. This month, we want to continue the story, but focus on Noel and his accomplishments of taming the harsh Australian Outback in a truck.

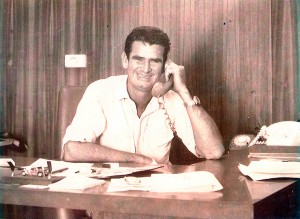

Noel Buntine had quite a reputation in the Australian Outback. Yes, he was good at business, but he was respected more for his good-humored optimism and his astonishing acts of human decency in times of trouble. Originally from Queensland and born on December 10, 1927, Noel Lytton Buntine worked in shipping in its eastern port of Rockhampton, as a tally clerk in Papua New Guinea, and then starting working in 1950 for the Mines Department in Alice Springs in Australia’s Northern Territory (NT).

No doubt having in mind that a bit of desert trail-blazing there in the geographical center of Australia would be nice, he began a transportation business with another public servant, John Ryan. Back then, they supplied and serviced mining equipment and were local agents for firms based in cities like Sydney. “In 1959, Buntine decided to move out of the Northern Territory and took a Commer Knocker called Baby Doll (a British truck) and one trailer, as part of his share of the business, and began running for Price’s Interstate Transport as a sub-contractor between Brisbane and Sydney,” wrote Stan Gibson in Big Rigs in February 1994. But, the way of life in the populated ‘eastern states’ wasn’t for him, and Noel was soon back in the Outback hauling cattle.

No doubt having in mind that a bit of desert trail-blazing there in the geographical center of Australia would be nice, he began a transportation business with another public servant, John Ryan. Back then, they supplied and serviced mining equipment and were local agents for firms based in cities like Sydney. “In 1959, Buntine decided to move out of the Northern Territory and took a Commer Knocker called Baby Doll (a British truck) and one trailer, as part of his share of the business, and began running for Price’s Interstate Transport as a sub-contractor between Brisbane and Sydney,” wrote Stan Gibson in Big Rigs in February 1994. But, the way of life in the populated ‘eastern states’ wasn’t for him, and Noel was soon back in the Outback hauling cattle.

Later, after being pushed out by some competition, Noel bought a B61 Mack and began hauling cattle into the Wyndham Meat Works on Western Australia’s far northern coast. His home was a tent and his office a briefcase behind the seat of his truck. This eventually improved to a house trailer to sleep in and a Holden ute (the SUVs of the day) for traveling to broken-down trucks. Ever down-to-earth, it was always a beaten up Ford F250 pickup rather than a shiny Merc he’d be seen in, even when wealth came along.

Road transporting of livestock was bound to replace traditional cattle droving on horseback, and Noel Buntine was part of this new order. During his first year, he moved 3,600 cattle and did odd jobs, like carrying 2,000 tons of fencing wire and posts to a five million-acre cattle station, on flatbed trailers. Sometimes, this fencing got so hot from the pounding sun, it was difficult to unload. The solution, wrote Gibson, was to “arrive at sundown, spray diesel on the surrounding trees and set them on fire, to provide the light to work by during the night.”

Road transporting of livestock was bound to replace traditional cattle droving on horseback, and Noel Buntine was part of this new order. During his first year, he moved 3,600 cattle and did odd jobs, like carrying 2,000 tons of fencing wire and posts to a five million-acre cattle station, on flatbed trailers. Sometimes, this fencing got so hot from the pounding sun, it was difficult to unload. The solution, wrote Gibson, was to “arrive at sundown, spray diesel on the surrounding trees and set them on fire, to provide the light to work by during the night.”

These outback roads were rough, and during ‘cattle shifts’ graders would come in. As for what could be called ‘main roads’ (which were graded annually), Gibson explained that they “had bull dust so deep there was a problem with dusted motors and the life expectancy of a wheel bearing was only about two trips. The drivers carried sealed boxes full of grease-packed bearings and they’d sometimes spend hours in the heat and dust belting the collapsed one with a hammer and cold chisel.”

Starting with just the one Mack truck, Noel made a habit of buying at least one extra prime mover and two trailers every year. He and his drivers would bounce along the poorly-maintained dirt roads, as only two NT main roads were paved (the Stuart and Barkly highways). “They would not see home base for months,” wrote Gibson, “and, on a couple of occasions, drivers would take delivery of a truck in Brisbane and, by the time Buntine saw the vehicle in person, it would already be on its second set of drive tires.”

Starting with just the one Mack truck, Noel made a habit of buying at least one extra prime mover and two trailers every year. He and his drivers would bounce along the poorly-maintained dirt roads, as only two NT main roads were paved (the Stuart and Barkly highways). “They would not see home base for months,” wrote Gibson, “and, on a couple of occasions, drivers would take delivery of a truck in Brisbane and, by the time Buntine saw the vehicle in person, it would already be on its second set of drive tires.”

Noel dealt with the vastness of the NT by establishing primitive ‘road train bases’ in the middle of nowhere to provide basic service and maintenance for the battered ‘B’ models, which pulled as many trailers as the clutch could handle. “Most of the work was carried out under the blistering sun in the summer and in below-zero temperatures in the colder months, as there were few structures to protect them from the elements.” Gradually, permanent depots were built in Alice Springs, Mount Isa, Wyndham, and Katherine. By 1981, Noel’s fleet had grown to 49 trucks and 150 trailers, making him the largest cattle-carrying operation in Australia.

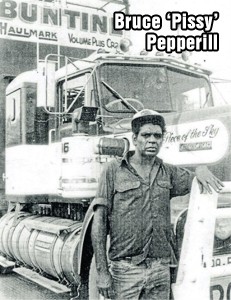

Noel Buntine was as big as the country he traveled. If outback drivers ran short of money in the days when a cash point was as rare as a drop of rain, they booked up their food, beer and cigarettes to Noel. Astute as he was, everyone knew he was as straight as they come. Even when money came along, he was never too big for his boots. He’d invariably be found having a beer in the front bar of the Katherine Hotel or at the tire depot in one of the bays with his men who, wrote Gibson, “were of all colors and persuasions and were judged on their ability to make a mile and nurse a truck and cattle.” One of them was an aboriginal driver named Bruce ‘Pissy’ Pepperill, whose favorite reply, when anyone asked if he was ‘an aboriginal’ was, “Just an original!” To work for Buntine, it wasn’t good enough just to know how to drive a truck. Men like Pepperill had to know how to handle cattle, repair a gearbox on the side of the road, sleep in a swag and fix their own meals, which was often a steak cooked on a shovel over the hot coals.

Noel Buntine was as big as the country he traveled. If outback drivers ran short of money in the days when a cash point was as rare as a drop of rain, they booked up their food, beer and cigarettes to Noel. Astute as he was, everyone knew he was as straight as they come. Even when money came along, he was never too big for his boots. He’d invariably be found having a beer in the front bar of the Katherine Hotel or at the tire depot in one of the bays with his men who, wrote Gibson, “were of all colors and persuasions and were judged on their ability to make a mile and nurse a truck and cattle.” One of them was an aboriginal driver named Bruce ‘Pissy’ Pepperill, whose favorite reply, when anyone asked if he was ‘an aboriginal’ was, “Just an original!” To work for Buntine, it wasn’t good enough just to know how to drive a truck. Men like Pepperill had to know how to handle cattle, repair a gearbox on the side of the road, sleep in a swag and fix their own meals, which was often a steak cooked on a shovel over the hot coals.

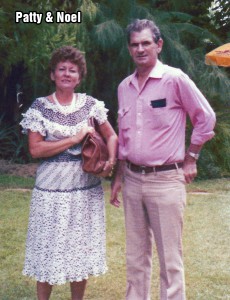

I asked Noel’s wife Patty, who helped me with this story and supplied most of the photographs, why Bruce was called ‘Pissy’ but she didn’t know. Patty spoke to me in May 2014 from her home in Katherine about Noel and their children, Jodie (who lives in Darwin and also helped me), Dennis (who died of cancer in March 2013), and Sterling (who owns a couple cattle stations, covering two million acres or so, with some 80,000 cattle and two or three road trains). I asked Patty what Noel was like but “he had his moments” was all she would divulge. But she could certainly recall the days when “he’d be away for a week or two, back and forth all the time. A bit hard if you’ve borrowed to start. Boom or bust,” she confided.

Noel not only led the charge, but he was brave with opportunities. He would say to his drivers, “If any of you see a business venture which has potential and all that is stopping you from going ahead is money, come and see me.” Gibson wrote: “The names of the men in the Northern Territory whose start was provided by a cash loan or bank guarantee from Buntine is virtually endless.” One was Dick David, who began as Noel’s yard boy before becoming a road train driver and then his operations manager, who turned a loan from Buntine into a multi-million dollar truck and fuel company, eventually buying Noel out when he retired! In turn, many of the men who benefited from Noel’s generosity often helped their own men into self-employment, as well, which started a nice ripple-effect.

Noel not only led the charge, but he was brave with opportunities. He would say to his drivers, “If any of you see a business venture which has potential and all that is stopping you from going ahead is money, come and see me.” Gibson wrote: “The names of the men in the Northern Territory whose start was provided by a cash loan or bank guarantee from Buntine is virtually endless.” One was Dick David, who began as Noel’s yard boy before becoming a road train driver and then his operations manager, who turned a loan from Buntine into a multi-million dollar truck and fuel company, eventually buying Noel out when he retired! In turn, many of the men who benefited from Noel’s generosity often helped their own men into self-employment, as well, which started a nice ripple-effect.

Noel himself felt the pinch in the early 1980s when he decided to sell his Buntine Roadways to a company in south-eastern Australia that became bankrupt within two seasons. Wrote Gibson: “Rumors spread across Australia that Noel Buntine had gone to the wall,” as those who were not in the know were unaware that Noel had sold the company. But Noel rolled on regardless.

Always pressing on, Noel continued on and bought 14 new Superliners from Mack Trucks, who’d kept faith in him during less profitable dry seasons. To seal the deal, Noel had to fly to Brisbane, but found the creeks flooded between his place and Katherine. Gibson wrote that “Patty drove him as far as they could go, then they swam and waded the creek where an employee, Alan Hobbs, was waiting with another vehicle.” Noel “changed into his city clothes on the side of the road then asked if there was a handkerchief in his vehicle. Patty re-crossed the creek, but all she could come up with was a roll of toilet paper.” Noel saw the funny side. “When I get to Brisbane,” he said, “I will be Mr. Buntine, but here at home I still blow my nose on a bit of dunny paper.”

Over the years, Noel was not always best pals with the Western Australian RTA (Road Transport Association), and in a move some drivers must have thought amusing, he called his new company RTA (which stood for Road Trains of Australia). Eventually retiring – or so he thought – to his family in Katherine along with their assorted animals, which included race horses, camels, donkeys and other pets, this new life wasn’t quite busy enough for Noel, so he took on some advisory jobs for the NT government.

Over the years, Noel was not always best pals with the Western Australian RTA (Road Transport Association), and in a move some drivers must have thought amusing, he called his new company RTA (which stood for Road Trains of Australia). Eventually retiring – or so he thought – to his family in Katherine along with their assorted animals, which included race horses, camels, donkeys and other pets, this new life wasn’t quite busy enough for Noel, so he took on some advisory jobs for the NT government.

The transport industry never forgot Noel Buntine. When he died at the age of 66 in 1994, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame (www.roadtransporthall.com) in Alice Springs, where the Buntine Pavilion was built to remember him. Even the road wants to remember Noel. The 354-mile Buntine Highway, named in his honor in 1996, runs from the Victoria Highway via Top Springs in the Northern Territory to Nicholson in Western Australia. As a reflection of how times change, Patty made the point that just as the nearby 244-mile Buchanan Highway was named after a traditional horseback drover, so the Buntine Highway was named after a ‘modern’ road train drover.

Hall of Fame organizer Liz Martin was born in Katherine and knew Noel when she was a child in Top Springs. “I can remember listening to a couple of old-timers who had run into hard times saying, it’s alright, Noel will be back next week, and if he’s got a few quid in his pocket, we’ll all have a quid,” she said. Commenting on Noel’s passing, Stan Gibson said, “I hope you took your checkbook with you, Buntine. The likes of Pissy Pepperill and other old Buntine drivers will be waiting patiently for you to buy them a drink!”

1 Comment

In about 1982 I was cycle touring in Australia and by the time I got near Wyndham in west Australia I was nearly broke, just my bicycle, camera and about $50. I stopped to chat with some blokes broken down on the side of the road in a fuel truck hauling to the Argyle diamond mine nearby(!). Since I was born the same year as Prince Charles, 1948, I introduced myself as the Prince. That got a laugh and broke the ice so then I described my predicament, cycling in the vast west Australia with very little money left. I needed work and they said go to Wyndham not far away, stop at Buntine Trucking and they would fix me up. So I did and when I first entered the Buntine office asking for a job they looked me over once and directed me to the door, but when I told them I was a ticketed welder they said “Welcome home, mate!”. Soon I was provided with accommodation, a room in a trailer, and began meeting my workmates, an amazing collection of personalities, a great selection of humanity tucked away in an isolated bit on the planet. Soon they made me feel at home and I settled in for several months.