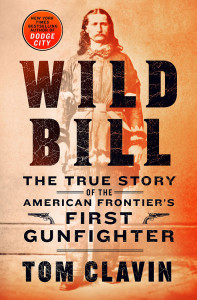

Ching. Ching. Ching. It’s high noon in your favorite Western movie, and that’s all you hear from the screen: seething wind and the ching of spurs on the ground as the hero struts to the shootout. The music is tense. It’s oh-so-dramatic. And it might’ve been (somewhat) true, as you’ll read in the new book “Wild Bill” by Tom Clavin. America’s first, most famous gunfighter was many things: sure-shot, scout, gambler and lawman, but for much of his life, he was not Bill. James Butler Hickok was born May 27, 1837, the last son of a shopkeeper who was in perpetually fragile health. Little is known about Jim’s childhood, but as a teen, Hickok left his family’s Illinois farm in search of a new western homestead. Finding a job was his first task when he landed in Kansas, but the state was struggling with issues of slavery so Hickok, an abolitionist who’d by then adopted the name “Bill,” may have joined forces with anti-slavery Free-Staters. This meant for him that “nowhere in eastern Kansas was safe” so Bill prodded further west, where he became a stagecoach driver and was known for his bravery, even before joining the Union in the Civil War. When the war was over, “The country had changed and (Hickok) changed with it,” says Clavin. Hickok returned to the plains, seasoned and with more of an edge – he’d become a legend, a killer with lightning-fast accuracy with any gun. Those, says Clavin, were all things that “marked” Hickok: every tenderfoot around wanted to prove his mettle against the “shootist.” And yet, Hickok continued to be a formidable force throughout his subsequent law career and his frontier adventures, despite that he was suffering from rheumatism and was going blind. He hid his afflictions well, though – or tried to – and they didn’t stop him from falling in love with a woman who was not, despite the legends, Calamity Jane. No, what stopped him were carelessness and a good streak at cards. Looking at the cover of “Wild Bill” you might expect that his tale is all you’d find in the pages here. Not so. Author Tom Clavin also gives a nod to every gunslinger and scout of Hickok’s time, and if that’s not catnip to Western fans, nothing is. This book sweeps cross-country, around Indian villages and through decades as it busts myths and sets records straight, pulling readers into cow towns and across prairies, and putting mis-truths to rest. We get dusty details, too, about jaw-dropping tales of frontier exploits, whether they were true or not. That allows this to be more than strictly a history book, as Clavin makes this tale seem as comfortable as a Saturday afternoon sofa-and-blanket session watching an old black-and-white western. Absolutely, “Wild Bill” is for fans of the Wild West, but it should also speak to anyone who likes frontier adventure. Look at that cover again. It should spur you to action!

Ching. Ching. Ching. It’s high noon in your favorite Western movie, and that’s all you hear from the screen: seething wind and the ching of spurs on the ground as the hero struts to the shootout. The music is tense. It’s oh-so-dramatic. And it might’ve been (somewhat) true, as you’ll read in the new book “Wild Bill” by Tom Clavin. America’s first, most famous gunfighter was many things: sure-shot, scout, gambler and lawman, but for much of his life, he was not Bill. James Butler Hickok was born May 27, 1837, the last son of a shopkeeper who was in perpetually fragile health. Little is known about Jim’s childhood, but as a teen, Hickok left his family’s Illinois farm in search of a new western homestead. Finding a job was his first task when he landed in Kansas, but the state was struggling with issues of slavery so Hickok, an abolitionist who’d by then adopted the name “Bill,” may have joined forces with anti-slavery Free-Staters. This meant for him that “nowhere in eastern Kansas was safe” so Bill prodded further west, where he became a stagecoach driver and was known for his bravery, even before joining the Union in the Civil War. When the war was over, “The country had changed and (Hickok) changed with it,” says Clavin. Hickok returned to the plains, seasoned and with more of an edge – he’d become a legend, a killer with lightning-fast accuracy with any gun. Those, says Clavin, were all things that “marked” Hickok: every tenderfoot around wanted to prove his mettle against the “shootist.” And yet, Hickok continued to be a formidable force throughout his subsequent law career and his frontier adventures, despite that he was suffering from rheumatism and was going blind. He hid his afflictions well, though – or tried to – and they didn’t stop him from falling in love with a woman who was not, despite the legends, Calamity Jane. No, what stopped him were carelessness and a good streak at cards. Looking at the cover of “Wild Bill” you might expect that his tale is all you’d find in the pages here. Not so. Author Tom Clavin also gives a nod to every gunslinger and scout of Hickok’s time, and if that’s not catnip to Western fans, nothing is. This book sweeps cross-country, around Indian villages and through decades as it busts myths and sets records straight, pulling readers into cow towns and across prairies, and putting mis-truths to rest. We get dusty details, too, about jaw-dropping tales of frontier exploits, whether they were true or not. That allows this to be more than strictly a history book, as Clavin makes this tale seem as comfortable as a Saturday afternoon sofa-and-blanket session watching an old black-and-white western. Absolutely, “Wild Bill” is for fans of the Wild West, but it should also speak to anyone who likes frontier adventure. Look at that cover again. It should spur you to action!