A landlocked country in South America, Bolivia has borders with Peru, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Paraguay. Its geography is an area of 424,200 square miles, but it used to be bigger. Through conflict and purchase, large portions of land have been acquired by Chile, Brazil, and Paraguay. With no access to a seaport and little rail to speak of, trucks are an important commodity, but the drivers typically drive old trucks, have little training, make meager wages, and travel on terrible roads.

Bolivia has no easy access to the sea, meaning road transport is crucial. Goods need to travel through Chile (the shortest route) or Peru to reach a seaport. Most of the world’s governments are sympathetic of Bolivia’s plight – except Chile. This predicament is seen as a stumbling block for the country, being dependent on Chile’s diluted goodwill for access to the South Pacific Ocean and shipping. After years of unsuccessful negotiations with various governments, Bolivia decided in 2011 to file a case with the International Court demanding that Chile negotiate an agreement so that Bolivia would have its own port again. However, in October of 2018, the court ruled that Chile is not legally obliged to negotiate with Bolivia on this matter.

Historically, Bolivia had about 300 miles of coastline, including the ports of Antofagasta, Cobija, Mejillones, and Tocopilla. After gaining independence from Spanish colonial rule in 1825, Chile and Bolivia entered treaty negotiations about borders. During these negotiations in the mid-1800s, the government of Bolivia gifted Chile 114 miles of said land. This sparsely populated area was rich in the natural fertilizer guano and also the nitrogen mineral saltpeter, which was highly sought to be used in agriculture, especially in Europe. Like a Klondike gold rush, Chileans flocked to the area to extract the deposits.

In February 1879, unsuspectingly, the Chilean army invaded Bolivia and won a military victory. After this event, Chile would claim all of the coastline, making Bolivia landlocked. As an act of compensation, Chile built a railway from the port of Arica to La Paz, which was opened in 1913. This very basic line carried passengers until the mid-1990s, and goods transport lasted until 2005. The railway is now closed. No one could have known how dependent we would become to road transport and having easy access to seaports. Bolivia is a poor country and, by their own admission, made poorer by this situation. It will be interesting to see if a solution to this age-old problem is ever found.

Bolivia has a population of 11 million people, and the capital is Sucre, located in the middle of the country. But because the government seat is located in La Paz, a city with 2.3 million residents, this is often confused as the capital.

The elevation of La Paz is 12,000 feet above sea level, and the city sits in a bowl, surrounded by the Altiplano Bolivian Plateau. Over the years, as the population increased, the only way was up for building housing and commercial property. For people to get to the higher reaches, a cable car system was built which began running in 2014. At first, even though the system receives large government subsidies, ordinary people (who it was originally built for) could not afford to use it. However, changes were made soon after to make traveling more affordable. The development is on-going and ambitious, as there will be a total of nine route lines of cable car systems when complete.

From La Paz, I made a visit to Lake Titicaca, the largest and highest navigable body of water in the world. To get there, the route went through the suburbs of the city of the neighboring El Alto, which is known as “The Rebel City” in Bolivia. Seen as a lawless place, there have been protests and resistance from the residents against a number of government acts, which even forced one president to resign. The law-abiding people of the city have their own way of tackling crime – by hanging ominous figures with pointed warning signs.

Most of the route is on dirt roads, but construction of a new road to the lake is ongoing. The lake, which counts as the number one tourist attraction in Bolivia, is heavily polluted. This is not visibly obvious to the tourists but has turned into a real problem. Raw sewage from nearby cities and mercury dumped into rivers which drain into the lake are just two sources of the pollution. A visit was also made to the large town of Copacabana, which is on the southern shore. Quaintly, this is where the cars, buses, and trucks are blessed by the priest of the church to give them good luck and protection from accidents.

When it comes to trucks, Volvo is king in Bolivia. While there, I saw an amazing number of secondhand trucks still working, most of them Volvos. The Swedish company is also well set up for the sale of new trucks, with a Bolivian dealer, and a manufacturing plant in bordering Brazil. There is also a dealer that sells Iveco and the Chinese brand JAC. Other Chinese brands like Dayun, CAMC, Sinotruk/Howo, C&C, and Foton are also present. Japanese manufacturers are well represented with dealers selling UD, Hino, and Toyota trucks. The Indian Tata Group set up a dealership in 2016, selling light and medium duty models. These, along with a heavy mix of all makes of U.S. trucks, make this part of Latin America very cosmopolitan.

One of the European truck makes rarely seen was DAF, however they are present, and the company has invested heavily in a new plant in Brazil. Scania built their first plant outside of Sweden in Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1957 and opened a facility in Argentina manufacturing gearboxes and differentials in 1976. The company boasts 103 dealers in just Brazil alone. Bolivia is oil rich, which makes the cost of diesel cheap, although the fuel price is heavily subsidized. The government decided to increase the cost by 83% a few years back but had to quickly rethink its decision after a major strike by trade unions occurred.

A lot of the trucking is privately run in Bolivia and, in terms of annual growth, is gaining momentum. A high percentage of drivers own their own truck, and the others drive for local transport companies. No different from anywhere else, the competition for loads is cutthroat. A survey carried out in the 1980s showed about 110,000 trucks in the country. There aren’t any current official numbers listed anywhere, but truck numbers recorded in 2013 were 410,000 and growing. As mentioned, everything travels by road, as there is very little railway infrastructure.

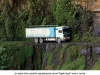

A top tourist attraction in Bolivia is the Yungas Road (aka Death Road) which is supposed to be a bicycle route out of La Paz to the Yungas region. All kinds of traffic use the road, which is deemed as one of the most dangerous roads in the world. The northern portion, which is mostly unpaved and without guardrails, was cut into the Cordillera Oriental Mountain in the 1930s. A fall from the narrow 12-feet wide “path” is as much as 2,000 feet in some places, and due to the humid weather from the Amazon there are often poor conditions like mudslides and falling rocks. Each year, over 25,000 cyclists ride along the 40-mile road, along with brave (or maybe stupid) car and truck drivers.

Truckers can apply for a license at 18 years of age and have to pass a written test only. The license is issued by local authorities in any of the nine states of the country. As good education is in short supply in Bolivia, generally, many of the drivers are poorly educated individuals. The roads in the country are mostly of poor quality, and only 10% of them are considered to be well paved routes. There is, however, a number of road construction projects going on.

The poor condition of the roads means drivers spend a longer time on their pickups and deliveries compared to drivers in other countries. The time taken is relative to speeds on the very poor roads, as well, with the average speed being about 12 mph. Also, because of the extra time taken, drivers are paid low wages, on average only $243 per month. Younger, inexperienced drivers are paid even less (about half this amount).

There seems to be scant regard for regular vehicle maintenance, which is the responsibility of the user, but this doesn’t seem to have any importance. Obviously, it’s a different story when there is a major component failure. It is thought that there is no requirement for a yearly inspection. Most trucks display their written registration number sign on each side of the cab for identification. Not surprisingly, the road accident death rate is very high – and growing each year. As car ownership is very low, it is no surprise that accidents involving trucks are commonplace. The lack of education plays a big part in this, with high occurrences of drunk driving.

If a driver in the U.S. (or most any other country) feels a bit weary, he might have a cup of coffee or a can of energy drink. In Bolivia, it is traditional for a driver to chew on coca leaves for stimulation. It is legal to do this in most of Latin America, and growing coca in peasant farming communities is on the rise. Most know this plant can become cocaine when the proper chemicals are added. The former President of Bolivia, Evo Morales, himself an ex-coca plant farmer, signed a law which would double the area allowed for growing coca. He also has long supported the legalization of coca leaf chewing globally, urging the UN to declare it legal.

Morales resigned his presidency in 2019 and fled to Mexico in fear of his life after a failed ploy of rigging an election. Today, Bolivia has a new president named Luis Arce who has unwittingly inherited Bolivia’s rapidly growing problems with drugs, among other things. Time will tell if the country improves, but one thing is certain – trucks (and their drivers) will always be a huge necessity in this ever-struggling landlocked country.