Zika – it sounds exotic, doesn’t it? But, sometimes the exotic can also be dangerous, as is this latest public health menace – the Zika virus. Like many viruses, Zika has been around for a while, but hasn’t been a threat in the United States – until now.

Zika – it sounds exotic, doesn’t it? But, sometimes the exotic can also be dangerous, as is this latest public health menace – the Zika virus. Like many viruses, Zika has been around for a while, but hasn’t been a threat in the United States – until now.

The virus is named for the Zika forest in Uganda where it was first recognized in 1947. There had been very few cases reported (although many had probably occurred) until 2015. Zika symptoms are very similar to those of other mostly-harmless diseases, so there were likely many cases that went undetected. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) alerted health authorities that Zika had been found in Brazil in 2015; previously it was only known to be in Africa, Pacific Islands and Southeast Asia. Now, it is found through most of South America, Central America and the Caribbean, as well.

Early this year there were many more cases of a rare birth defect called microcephaly (micro=small/cephaly=head) in Brazil, and many more cases than usual of Guillain-Barré syndrome in Latin America. Both of these nervous system disorders are believed to be caused by the virus. Microcephaly keeps the brain from developing normally and can cause early death. Guillain-Barré syndrome can cause paralysis. The paralysis may be temporary or permanent, and can even affect your ability to breathe. No one knows for sure if the Zika virus causes these neurological disorders – all we can say right now is that there are more cases being seen since the Zika virus has been spreading.

So, how do you get the Zika virus? The virus is carried in the body of the Aedes mosquito – the mosquito bites a human being and the virus gets into the person’s body through the hole the mosquito made in the skin. The mosquitoes that carry Zika can bite during the day, as well as at night. A pregnant woman who is infected may pass it to her baby. Zika can also be transmitted through sexual activity. Although it has not occurred in the United States, Zika can also be passed to others through blood transfusions. It is unclear if it can be passed via saliva or urine.

How do you know if you have the Zika virus? Therein lies the problem. Zika may not cause any symptoms in some people (only 1 out of 5 people have symptoms), or symptoms are so mild that the infected person wouldn’t make a trip to their healthcare provider because of them. Symptoms can be mild rash, redness of the eyes, joint pain, fever, muscle pain and/or headache. You might get some or all of these, or none of them. And, these are the same symptoms you might get for about a hundred other diseases. There is a blood test for Zika, but it must be done in the first week of the illness, in a special laboratory, which makes it a lot more complicated. The most effective way to fight Zika is to prevent it in the first place.

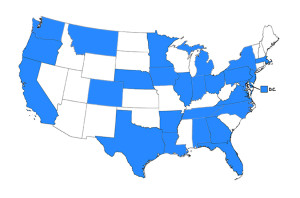

Why would a trucker need to know about Zika? Well, for one, it’s spreading throughout the United States rather quickly – there have been travel-associated cases reported in over half of the 50 states by people who have traveled outside the U.S. and gotten sick with Zika virus, and then come home with it (see map – the blue states have reported cases of Zika). There have also been several locally-acquired cases reported in the warm, tropical territories of the U.S. – like Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa. There are even a few cases in Canada, now.

Why would a trucker need to know about Zika? Well, for one, it’s spreading throughout the United States rather quickly – there have been travel-associated cases reported in over half of the 50 states by people who have traveled outside the U.S. and gotten sick with Zika virus, and then come home with it (see map – the blue states have reported cases of Zika). There have also been several locally-acquired cases reported in the warm, tropical territories of the U.S. – like Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa. There are even a few cases in Canada, now.

Just like with lots of other infectious diseases, the Zika virus can move from place to place. Truckers drive across the country and, oftentimes, into neighboring countries. They can also take a vacation to an exotic destination and then bring Zika home with them. If a trucker gets bitten and infected in Texas, and then drives to Florida and gets bitten again by another mosquito, that Florida mosquito can now get Zika into its body from the Texas trucker. And, when it goes off to bite another poor, unsuspecting person, Zika can be spread. And on and on it goes. You can see how someone like a trucker, who is constantly moving from state to state, could spread the virus.

The best way to prevent the spread of Zika is to avoid being bitten by mosquitoes. The mosquitoes that cause Zika infection are in the United States – and just about everywhere else. Using an insect repellent with DEET can keep the bugs off of you so you don’t get bit (make sure to use an EPA-approved repellent that is safe for pregnant women or permethrin on clothing – don’t put it directly on your skin). If you can, stay in air-conditioned places or places where there are door and window screens to keep insects out. Long sleeves and pants will also limit the opportunities for mosquitoes to bite. Be sure to get rid of standing water where mosquitoes breed – old tires, garbage cans, flowerpots – anywhere that water can collect creates a risk.

Women who might get pregnant need to be especially cautious. Even though it has not been proven that Zika can cause microcephaly, there is enough evidence that one ought to be extra careful, especially if already pregnant. Since Zika is also sexually transmitted, men and women should take extra measures to protect themselves (like using a condom). Right now, the only treatment for the Zika virus is to treat the symptoms – aspirin or acetaminophen for fever and body aches, lots of fluids and rest. It usually goes away within a week or so, and it appears that most people do not get it a second time.

If you feel like you might have symptoms of Zika, even if you can’t have a blood test done, follow the steps above to avoid being bitten by more mosquitoes. If you don’t pass Zika to the next mosquito, the mosquito can’t pass it to another person. So, whether you are on the road for work or for fun, make sure you are not hauling Zika!